L'Autorità Garante della Concorrenza e del Mercato, in data 26 luglio, ha autorizzato con condizioni…

Eu Commission: “Research funding boosts scientific excellence and competitiveness”

The European Commission has published its ex-post evaluation of the 7th Framework Programme (FP7), the EU’s research funding programme between 2007 and 2013. The evaluation is based on a report by an independent group of high level experts, as well as the Commission’s response to its recommendations published in two legal documents. The main findings are that FP7 was effective in boosting excellent science and strengthening Europe’s industrial competitiveness, contributing to growth and jobs in Europe. The evaluation also identified ways to improve how the EU funds research and innovation, of which many issues are already being taken up by Horizon 2020, the successor programme to FP7.

- FP7 was particularly effective in strengthening scientific excellence. FP7 projects have so far generated 170,000 publications, with an open access rate of 54% for all scientific peer reviewed publications created during the life time of FP7. The share of publications that is in highly-ranked journals lies above the EU average. In some programmes up to 30% of publications arising from FP7-funded projects rank among the top 5% of highly-cited publications in their disciplines – well above the European and US averages. More than 1,700 patent applications and more than 7,400 commercial exploitations have so far resulted from FP7 projects. FP7 promoted ground-breaking research through the European Research Council (ERC). The numbers of publications in top-rated scientific journals that acknowledge ERC funding, as well as the number of Nobel Prizes and Fields Medals received by ERC grantees, all demonstrate that ERC grants have quickly become a hallmark of scientific excellence.

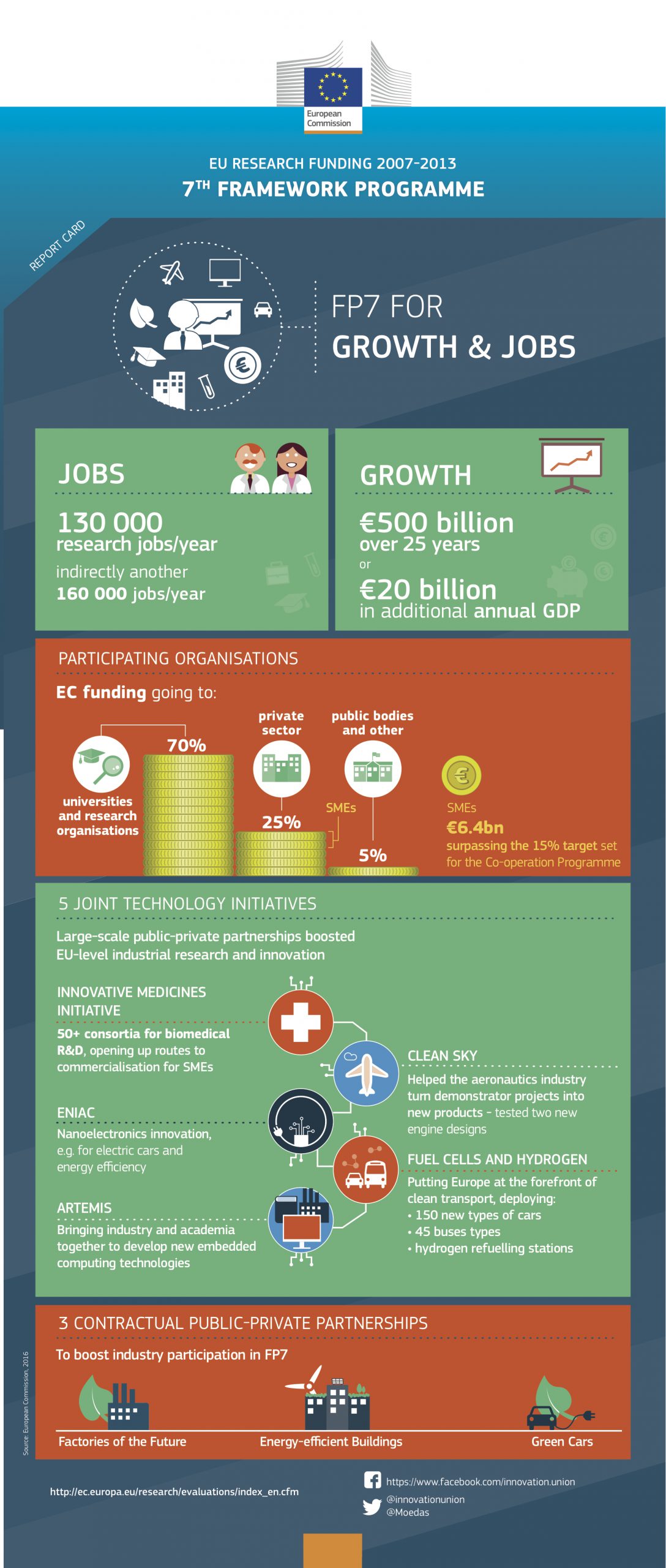

- FP7 contributed to increasing the competitiveness of Europe’s industry. Over the course of FP7, the participation of private partners increased. The Joint Technology Initiatives and other Public-Private Partnerships boosted industry participation, made it possible to realise strong leverage effects that contributed greatly to the competitiveness of Europe’s industries in areas as diverse as pharmaceuticals, aeronautics and fuel cells and hydrogen. In addition, the Risk-Sharing Finance Facility improved access to loan finance for research and innovation-focused companies through loan agreements worth €11.3 billion that were signed with more than one hundred companies.

- FP7 had a positive impact on growth and jobs. Given that FP7 only accounts for a relatively small proportion of total public RTD expenditure in Europe, its economic impacts are substantial, through the leverage effect of various instruments, impact on GDP and effects on employment. It is estimated that FP7 will increase GDP by approximately €20 billion per year over the next 25 years, or €500 billion in total through its indirect economic effects and create over 130 000 research jobs per year (over a period of 10 years) and 160,000 additional jobs indirectly per year (over a period of 25 years). There is also evidence of positive impacts in terms of micro-economic effects with participating enterprises reporting innovative product developments, increased turnover, improved productivity and competitiveness. It is however too early to make a final assessment of the market impact of FP7 projects.

- FP7 addressed transnational societal challenges. E.g. in the area of energy, ICT, environment, health, food safety, climate change, security, employment, poverty and exclusion and facilitated the establishment of a common scientific base in these areas, which addresses societal challenges that could not have been fully resolved by single countries alone.

- FP7 trained and involved leading international scientific and technological talent. FP7 was an open system that allowed more than 21,000 new organisations to receive EU funding. FP7 strengthened the training and long-term mobility of researchers, enhanced the quality of doctoral training and helped improve working conditions for researchers in the EU. FP7 supported 50,000 researchers, including 10,000 PhD candidates from 140 countries (of which more than a third were fellows from third countries). The programme stimulated the mobility of researchers across Europe. It also contributed to sustainable employment for researchers in Europe and helped increase the participation of women researchers and of international researchers in beneficiary research teams.

- FP7 was effective in fostering inter-disciplinary research and increased Europe-wide research and innovation collaboration and networking. Collaborative research projects brought together players from different disciplines and the share of researchers participating in projects from different priorities almost doubled over the course of the Programme, leading to durable inter-sectoral collaborations.

- FP7 made substantial progress as regards the gender dimension. Under FP7, a target of 40% of the under-represented sex was set for experts’ panels and other groups. The overall proportion of women evaluators was slightly higher than the target (40.4%). In total 38% of the workforce of FP7 were women. At the same time, the High Level Expert Group report found that in FP7 the share of female project coordinators was 19.2%, showing that whilst progress has been made, ‘glass ceiling effects’ persist.

- FP7 contributed effectively to increasing the level of research investment. It did so notwithstanding the difficult economic situation in the latter part of FP7. Between 2007 and 2013, the share of EU-28 GDP dedicated to R&D increased, with FP7 compensating for the sharp decline in national public funding for research and innovation in certain Member States. According to the external evaluation of the High Level Expert Group, through short-term leverage effect and long-term multiplier effects each euro spent by FP7 generated approximately €11 of estimated direct and indirect economic effects through innovations, new technologies and products.

- FP7 engaged SMEs strategically, with funding of around €6.4 million, above the 15% target for the FP7 cooperation programme. Results of econometric analyses show that SMEs participating in the FP7 scored 38% higher than the control group with regard to employment growth and operating revenue.

- FP7 was open to the world involving participants from 170 countries. It widened EU participation and contributed to the achievement of ERA. On average in FP7 collaborative projects, 11 organisations from six different countries and nine different regions participated.

- FP7 enhanced the alignment of research activities between Member States. It achieved this through common strategic research agendas, aligned national plans and joint calls. Initiatives to coordinate and integrate national programmes mobilised over €2.75 billion in national funding.

- FP7 provided the knowledge base to support key EU policies. To date, there are more than 350 cases where FP7 projects have been exploited for policy support. FP7 also led to more than 550 standards and contributed to EU flagship initiatives through more than 1,700 patent applications.

The ex-post evaluation of FP7 has highlighted certain shortcomings in the implementation of FP7:

- FP7 could have further improved large-scale simplification: The level of complexity of FP7 was unsatisfactory. Although the measures introduced during the course of the Programme on a piecemeal basis proved beneficial, the variations in rules and procedures between different parts of the Programme hindered its efficiency. This is demonstrated in part by the high error rate associated with FP7.

- The different parts of FP7 programme operated too much as isolated silos. Although FP7 had a transparent structure around four Specific Programmes with explicit priorities, the different components of the Programme were unduly rigid. This led to inefficiency due to overlaps between the objectives of different parts of FP7’s Specific Programmes.

- FP7 was not effective in building synergies with related European funding programmes. One of the goals of FP7 was to ensure complementarity with other programmes such as the CIP and the EIT, as well as the Structural Funds. However, the separate legal bases and differences in implementation rules meant that progress was more limited than required. The Commission is already addressing these and other recommendations in Horizon 2020.

In total FP7 136,000 eligible proposals were submitted to FP7 calls for proposals, from which 25,000 projects were funded. FP7 had a vast group of participants with more than 134,000 participations from 170 different countries. The participations came from in 86% of the cases from EU countries, 8% from Associated Countries and 6% rest of world. In total 29,000 organisations participated, of which over 70% were newcomers. Of these universities and research organisation received 70% of the funding; 25% private sector, of which half to SMEs, and 5% to public bodies and others. In total SMEs received €6.4 billion in FP7. Many of the projects supported by the €28.7bn Cooperation programme are leading to new processes, technologies and products that will be good for the economy and help improve people’s lives and tackle our biggest challenges. For example:

- Independent experts pointed out that the scientific impact is particularly strong for the Information and Communication Technologies programme, which invested €7.9bn in 2328 projects. Academic areas such as artificial intelligence, Internet of Things, media, and quantum computing were cited as good examples for advancing the state of the art. €4.8 billion was invested in 1,008 projects in the field of Health. Achievements include new screening methodologies in diabetes and Alzheimer’s disease; a portable PET scan that was brought to market in three years; an oral test for the diagnosis of breast cancer; and more rapid identification of new therapeutic targets in areas of autism and schizophrenia. These will contribute to speeding up the development of new medicines in Europe.

- 374 projects were funded with €1.9 billion in the field of energy research in renewable energies such as wind, solar and biomass, addressing the performance of materials and hydrogen storage, in order to improve energy efficiency and the security of supply and to reduce pollution.

- The Environment programme addressed environmental, climate change and resource efficiency issues with projects on, for example, earth observation, assessment tools for sustainable development and environmental technologies. A total of 494 projects were funded with a €1.7 billion contribution from FP7.

- The Security programme stimulated European security research and contributed to reducing the fragmentation of the research community. In addition to the direct benefits resulting from projects, including in the fields of disaster management or societal impacts, FP7 Security research engaged more end-users in projects, created end-user communities and contributed to standardisation activities. A total of 319 projects were funded with €1.3 billion from FP7.

- The Clean Sky Joint Undertaking stimulated action to meet targets for reducing emissions and noise in air transport in Europe set by the Advisory Council for Aeronautics Research in Europe (ACARE) in Vision 2020. For instance, technologies developed within the Green RotorCraft demonstrator (helicopters and tilt-rotor aircraft) have resulted in a reduction of 30% for CO2 and 47% for noise compared to the respective targets of 25% and 50% reduction. A total of 474 projects were funded with a contribution of €1.9 billion from FP7.

Many issues raised by the High level Expert Group have already been addressed in Horizon 2020, but a number of specific points will be further addressed in the years to come. For instance, the European Commission will:

Many issues raised by the High level Expert Group have already been addressed in Horizon 2020, but a number of specific points will be further addressed in the years to come. For instance, the European Commission will:

- Implement a new strategic focus for Horizon 2020 in order to maximise its contribution to the Commissioner Moedas’ objectives of ‘Open Innovation, ‘Open Science’ and ‘Open to the World’; Facilitate the elaboration of important projects of common European interest, which can foster vast deployment of research into mature technologies.

- Use the Policy Support Facility and Cohesion Policy capacity building support to assist Member States in implement effective reforms of their research and innovation systems;

- Continue to foster synergies between Horizon 2020, the Structural Funds and LIFE, and report on this issue in the context of the Horizon 2020 interim evaluation; Promote potential synergies with the European Fund for Strategic Investments (EFSI);

- Ensure that new Commission proposals are ‘fit for innovation’ by applying the ‘Better Regulation’ Guidelines, and in particular the ‘Research and Innovation Tool’ of the impact assessment guidelines;

- Improve the framework conditions for better innovation ecosystems in the EU;

- Continue to identify and implement simplification measures;

- Ensure data quality and coherence to strengthen monitoring and evaluation systems, in line with the ‘Better Regulation’ requirements;

- Support Member States in the national evaluation of the impact of EU Framework Programmes;

26 gennaio 2016